1887-1954White earthenware with terra sigillata, cobalt sulfate, cobalt underglaze and clear glaze

A few blogs ago I mentioned that I was working on a review

of Michael Flaherty's exhibition at the Craft Council Gallery for C

magazine. While I was working on

it I was surprised to discover how many folks here in St. John's were

unfamiliar with the publication.

In my opinion, it is Canada's best publication in terms of critical

writing about art and it certainly deserves our attention.

Here's a link to their website if you'd like to check it

out:

Anyhow, with the editors' permission I am sharing the text

of my review, which appears in C magazine's current Summer 2012 issue.

My favourite image of Mike as a Grey Island settler.

Michael Flaherty: Rangifer Sapiens

Craft Council Gallery, St. John’s, NL

February 4 – March 11, 2012

Artist Michael Flaherty describes

himself as a “conceptual ceramicist” and occasionally as a “ceramic

fundamentalist.” Both self- identifications distinguish his studio practice

from functional pottery and highlight the fact that Flaherty is part of a new

generation of craft practitioners who are as interested in ideas as they are in

materials or objects. Leading craft theorist Glenn Adamson characterizes this

generation of makers as “post-disciplinary” because they work across

disciplines normally distinguished by

a medium such as ceramics. This is a

radical departure in the evolution of studio craft practice. Among his

post-disciplinary peers, Flaherty stands out as “ceramic fundamentalist.” He is

engaged with ceramics but maintains a critical distance from it.

When Flaherty embarked on a self-imposed

exile on one of the abandoned Grey Islands off the north coast of Newfoundland

in 2009, he captured the public’s imagination. Why would a young, thirty

something artist leave the comfort of his studio and community in downtown St.

John’s for the isolation of a remote island? Ostensibly, the three-month

project was a self-styled artist residency wherein he set out to “create and

document a location specific art piece.” In his presentations before and after

the event, Flaherty explained that he was there to build an inside-out kiln. It

was a conceptual art event where he would symbolically “fire the island.” In

his blog-commentary about the Grey Islands, Flaherty shows himself, the urban

potter, decked out in buckskin jacket and coonskin cap, like a campy 2009 version

of “a settler.” The title of the resulting show, Rangifer Sapiens translates

from scientific Latin as “wise caribou” and it features haunting ceramic

sculptures. They are milk-white, life-sized antlers that grow with organic

grace from broken pottery—cups, plates and teapots, usually left with a loop of

functional handle. Each “shard” is blushed with rust tones and it appears that

the decoration of decal or hand-painted motif has migrated from vessel to

antler, leaving its imprint. The fascinating result is a rich, ambiguous hybrid

object of human and animal, like a mythological creature that simultaneously

taps into two interconnected worlds. All of the sculptures in the show are

titled by numbers—birth and death dates—found on gravestones in French Cove.

These titles hint at the personal and encourage the interpretation of the works

as portraits.

Effectively, Flaherty’s invention of

antler-shards is a timeline of the habitation of the Grey Islands. From the

1500s onwards, cod, herring and seals attracted French fishermen and ultimately

English and Irish settlers to these remote islands. However, by the 1960s, the

population of the islands had shrunk from about 200 to 86 souls.

They were resettled to White Bay, which

was deemed more easily administered by the provincial government. In the early

70s, a herd of caribou was introduced to the Grey Islands by the Department of

Wildlife to save them from extinction due to overhunting by the non-Aboriginal

population, who least needed the caribou for subsistence. During his three

months on the Grey Islands, Flaherty repeatedly found shed antlers from the

living herd and the archaeological remains of the place’s human past. The

implications were not lost on him.

Flaherty’s response to the historical

narrative of the Grey Islands’ habitation is especially interesting because of

the artist’s age and perspective. He is a generation removed from the

hot-button topic of resettlement in the province, and two generations removed

from Newfoundland joining Confederation. There are many layers to his

complicated and intelligent response. On one hand, Flaherty’s vantage point

gives him a sobering perspective that his father and grandfather’s generation

could not easily enjoy. The questions of whether Newfoundland should join

Confederation (and Canada) and whether the government had the right to resettle

its rural population were topics of fiery debate, which for decades dominated

the province’s cultural identity and threatened to divide families.

Resettlement, for exam- ple, was widely regarded as the deathblow to the

traditional outport lifestyle that today is the staple icon of the province’s

tourism ads.

Flaherty has noticeably avoided the term

of “resettlement” in his media inter- views and artist statement. His art points

out the human-centric weakness of earlier dialogues on this topic. Succinctly

put, it says: where human civilization stops, nature flourishes. It is a subtle

wake-up call to a province that has only in the past two years introduced a

curbside recycling program in its capital city. In other provinces, it is

likely that this body of Flaherty’s work will be seen in terms of colonialism

and relevant to a discussion of the residential schools and forced resettlement

of Aboriginal youth.

Flaherty’s ability to draw a “connection

between past and present, human and animal, presence and absence,” as he sets

out in his show statement, is impressive. Flaherty’s ceramic sculptures have a

sur- prising, nuanced wholeness, both visually and metaphorically. The fusion of

antler and cup assumes a visual logic; they are not awkward or jarring. He is

able to communicate that the shed antler, which is scientifically classed as

“true bone,” emerging from the skull of the animal is metaphorically equivalent

to the shard or “true bone” of the human. The “shard” portions of the

sculptures are thrown on a potter’s wheel and then cut with careful precision.

They are not broken or damaged. The

“shards” are fragments worn smooth with time and the elements. The language of

European settler ceramics and successive contemporary counterparts are

documented on the antler portions not as interrupted pattern but in continuous

passages that wind around its front and back.

Flaherty’s sculptures function in the

manner of a quoted line of poetry: they are sections but are not broken. In

fact, some of the decorations are miniature landscapes, which Flaherty has said

are of imagined places. The silhouettes of cobalt blue waves or rolling hills

echo the profile of the antler’s tines. It is a subtle act of reciprocation.

Gloria Hickey is an independent curator and writer living in St.

John’s, NL. Her most recent touring exhibition is The Fabric of Clay: Alexandra

McCurdy.

First published in C

Magazine issue 114 (Summer 2012)

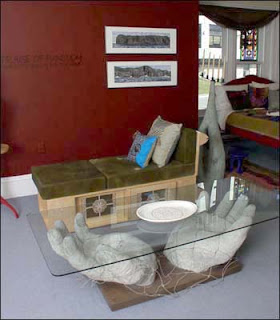

Mike with an installation of his antler shards.